Chromatography is a laboratory technique for separating the components of a mixture. It is carried out by dissolving the mixture in a fluid called 'eluent'. The fluid, by transporting the components along a carrier, allows them to stratify at different positions in the carrier. The different stratification of the components is due to their different velocities, which therefore results in their separation during the transport of the eluent fluid.

The chromatography process consists of two phases, the stationary phase, that of the support, and the mobile phase, that of the solvent. The different affinity of the mixture components in the two phases is the fundamental principle on which chromatography is based.

Typologies of chromatography

Chromatography can be carried out using various techniques, the main ones being: column, paper, thin-layer.

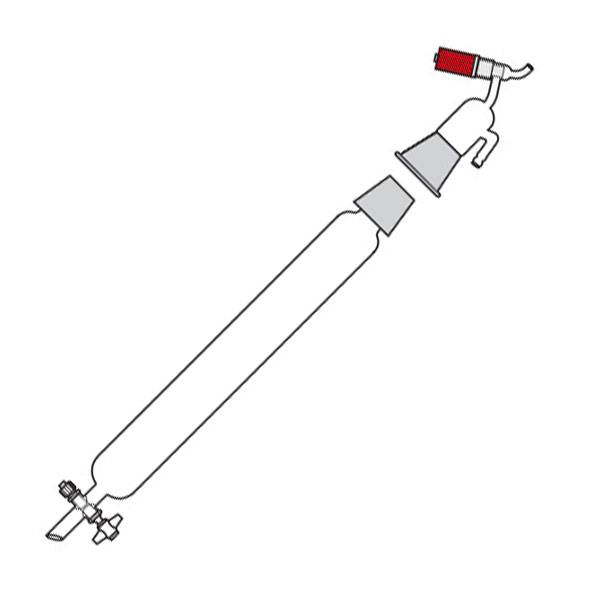

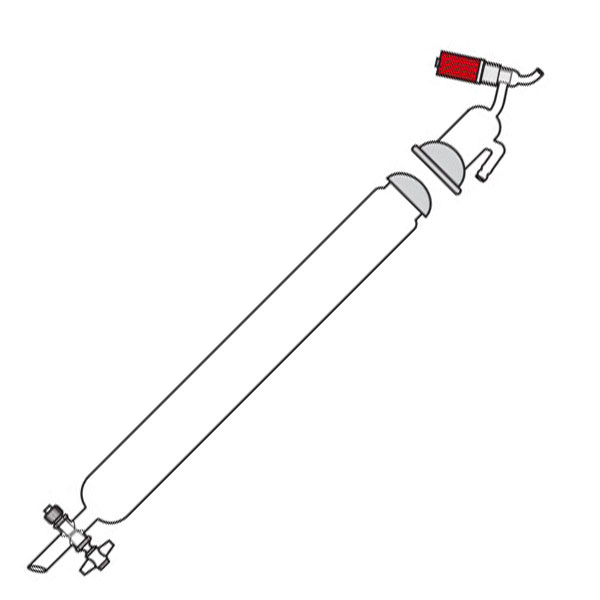

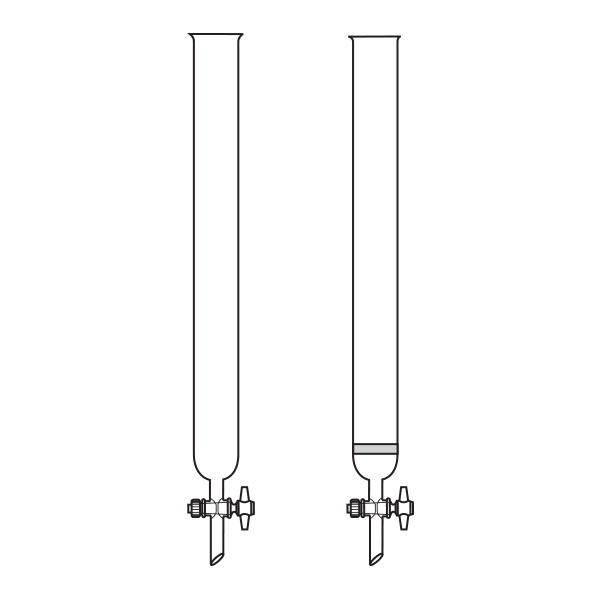

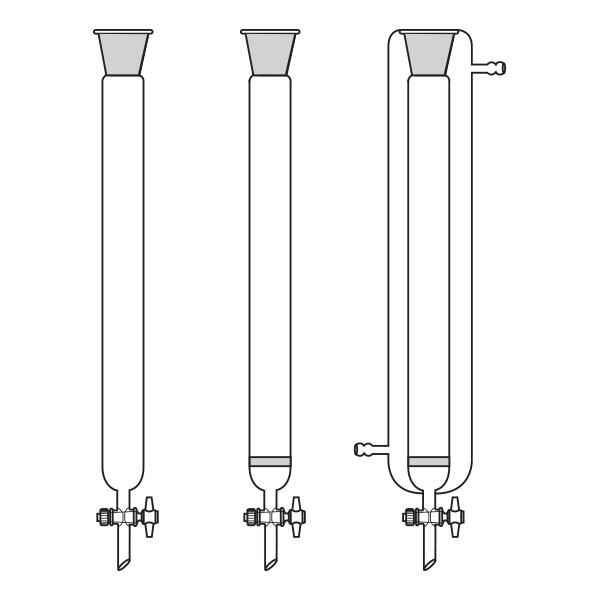

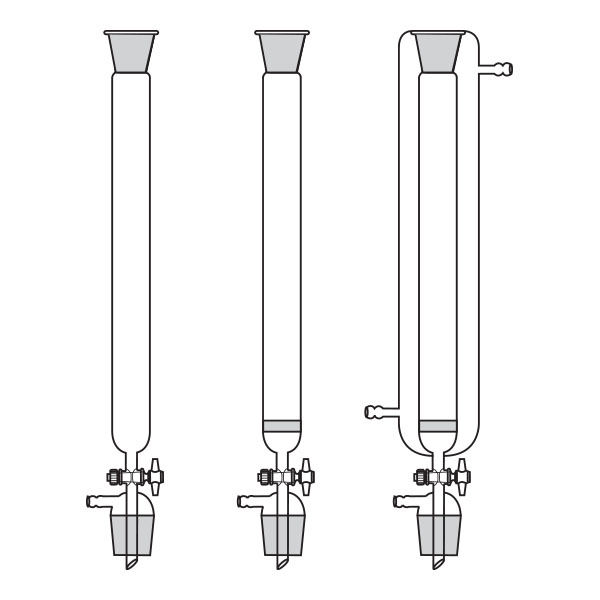

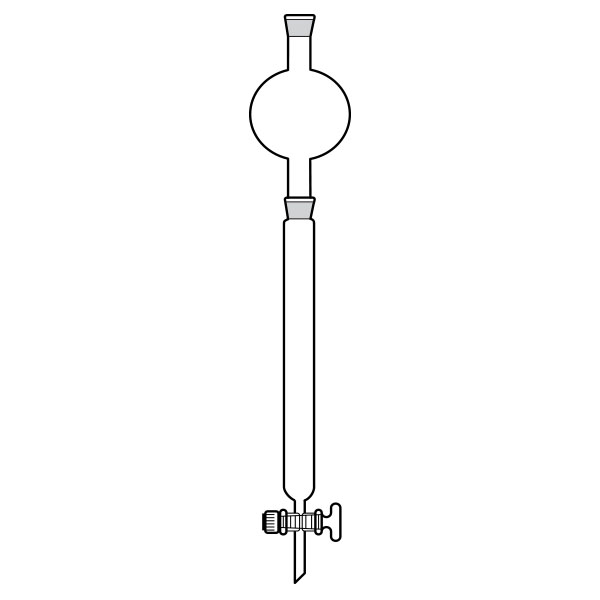

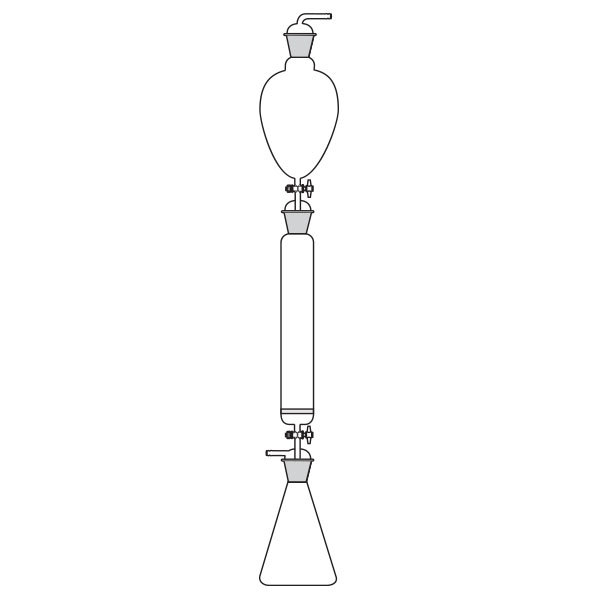

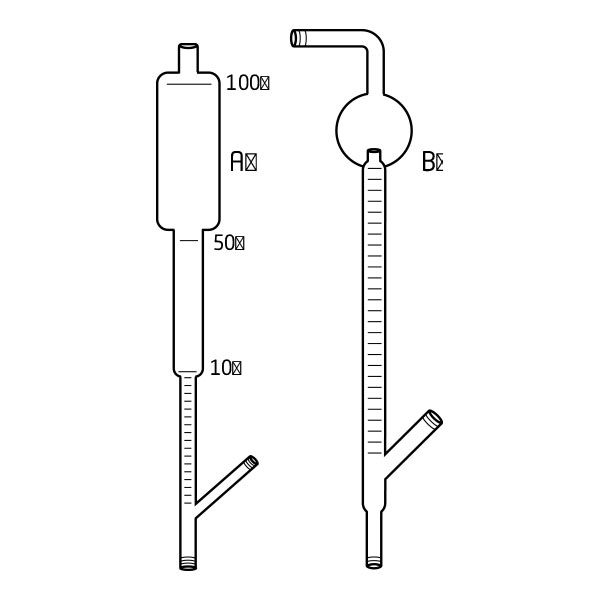

Chromatography-on-column

Chromatography-on-column

This was the first type of chromatography in which the stationary phase is located inside a glass tube. The components of the mixture are inserted at the upper end of the glass tube. Subsequently, they are deposited along the walls of the column as they descend. This is due to the different speed with which the mixture components are dragged in mobile phase towards the lower end of the column.

Chromatography-on-paper

Chromatography-on-paper

This type of chromatography is characterised by the fact that the stationary phase consists of a strip of filter paper, on the edge of which the solution to be separated is deposited. The filter paper is then placed in a container with solvent. As the solvent rises along the filter paper, it collects the solution to be separated. This is subsequently separated along the paper during the transport of the solvent.

Thin Layer Chromatography, or TLC (Thin Layer Chromatography)

.

It differs from paper chromatography in that the stationary phase, instead of being composed of a layer of filter paper, is a thin layer of adsorbent material deposited on a glass plate. Compared to paper chromatography, thin-layer chromatography also allows more precise and faster separations. Consequently, the equipment for performing chromatography can be varied. From glass for column chromatography, to cellulose layers.

However, there are different criteria according to which chromatography techniques are identified. For example, there are techniques identified according to the physical state of the mobile phase.

Liquid Chromatography (LC)

Liquid Chromatography (LC)

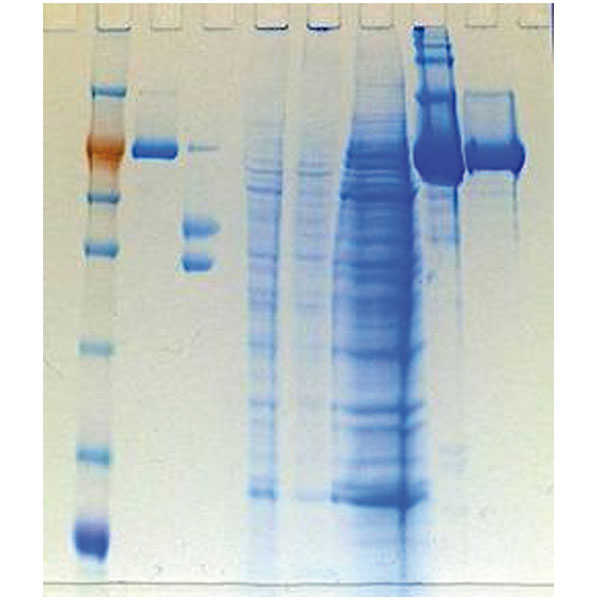

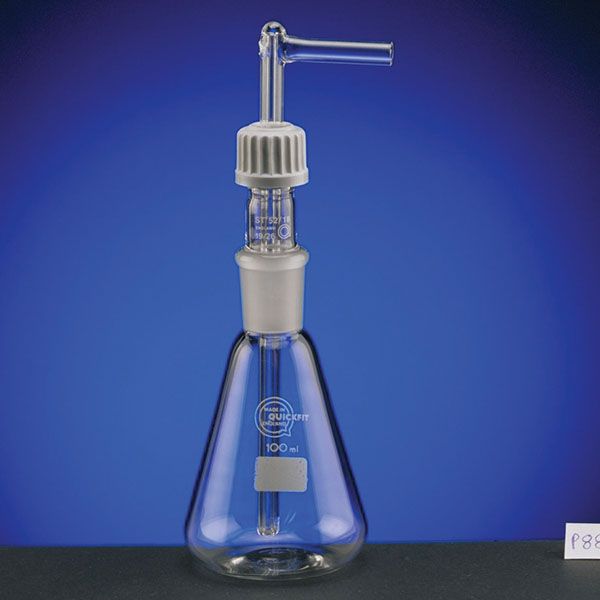

An example of this is liquid chromatography. This is a separation technique in which the mobile phase is a liquid. It can be performed either in a column or in a plane. Today's liquid chromatography, which usually uses very small packing particles and a relatively high pressure, is referred to as high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

In HPLC, the sample is propelled by a liquid at high pressure (the mobile phase) through a column filled with a stationary phase consisting of irregular or spherical particles, a porous monolithic layer or a porous membrane. At the end of the column, a detector and a computer allow continuous analysis to quantify and identify the injected substances by means of a chromatogram.

There are, in addition, techniques identified by separation mechanism.

Ion chromatography (IC)

Ion chromatography (IC)

Also known as ion exchange chromatography, ion chromatography is itself a liquid chromatography. It allows concentrations of ionic species to be measured by separating them based on their interaction with a resin. Ionic species are separated according to their size and type of species. Sample solutions pass through a pressurised chromatographic column where the ions are absorbed by column constituents. Then an ion extraction liquid, known as an eluent, passes through the column, and the absorbed ions begin to separate from the column. The retention time of different species determines the ion concentrations of the sample.

What chromatography is used for

Chromatography mainly serves two needs:

- serve for analytical purposes, i.e. to analyse a mixture and separate the substances from which it is composed in order to isolate the various components;

- serve for preparative purposes, i.e. to separate the various substances present in a mixture to obtain pure substances;

.

In any case, it always involves breaking down a mixture, or rather a solution, so we can call it a separation technique.

Chromatographic techniques are almost always destructive.

This means that the material analysed must be dissolved in a liquid solution or vapour phase. In many cases, this can be a problem.

In fact, if you want to analyse ancient or particularly valuable artefacts, such as the linen cloth of the Holy Shroud, the chromatographic technique would not be suitable.

Chromatographic analysis is not possible without taking a sample.

The upside, however, is that the amount of sample required is very small.

1 ml to 1 µl of solution is sufficient, which corresponds to a few mg of solid sample.

The chromatographic technique is not possible without taking a sample.

The upside is that the amount of sample required is very small.

The amount of sample required is very small.

For example, it is possible to analyse the substances used to dye textiles in antiquity.

The identification of various dyes is only possible, however, if one has the composition standards of already known substances.

In order to be able to make a comparison, it is necessary to have information on as many substances as possible.

For example, substances from insects were very often used for certain colours, even in mixtures with each other.

The resulting colour was obtained from the contribution of several dye substances, often held together by other binding and preserving substances.

The colour of the insects was also obtained from the use of a mixture of dyes.

Or, to cite another case, thanks to chromatography it was possible to determine the nature of food residues found in a Roman archaeological site.

The results showed:

- pyrrole and toluene as markers for proteins;

.

- furan as a marker for carbohydrates;

- organic acids as markers for fats, waxes and oils;

Thanks to this instrument, it is possible to provide answers that were unthinkable until the last century.

Chromatography-on-column

Chromatography-on-column Chromatography-on-paper

Chromatography-on-paper Liquid Chromatography (LC)

Liquid Chromatography (LC) Ion chromatography (IC)

Ion chromatography (IC)