In laboratory chemistry, taps are extremely common. They are used, for example, on equipment such as ramps or burettes. They essentially act as a shut-off and opening for controlling a liquid or gas in chemical instrumentation. Taps do not have the same characteristics as valves, so many models are limited to an on/off function.

Structure

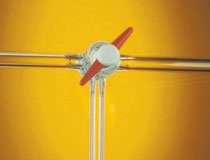

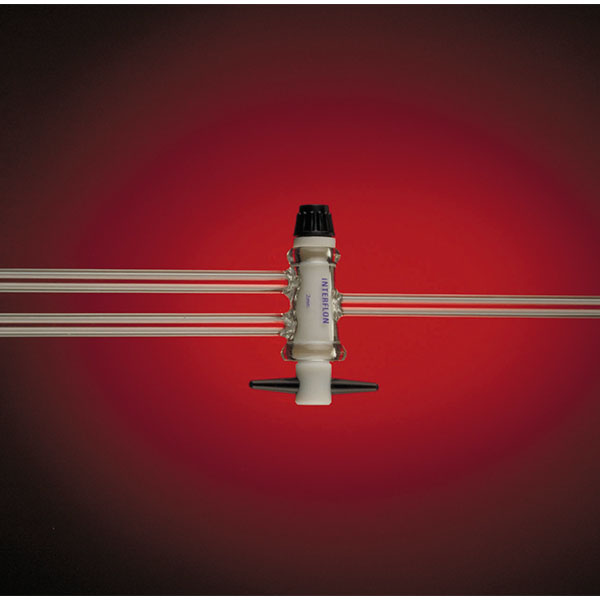

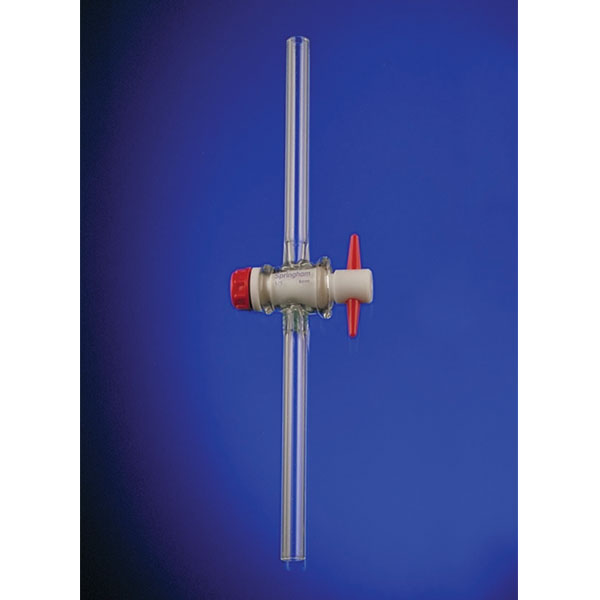

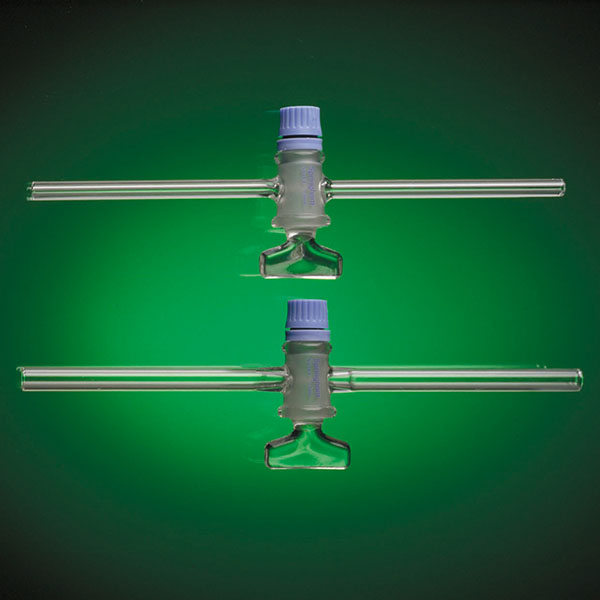

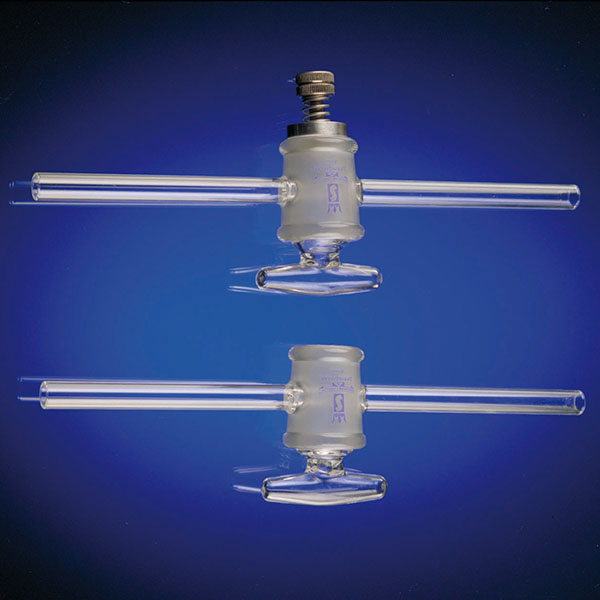

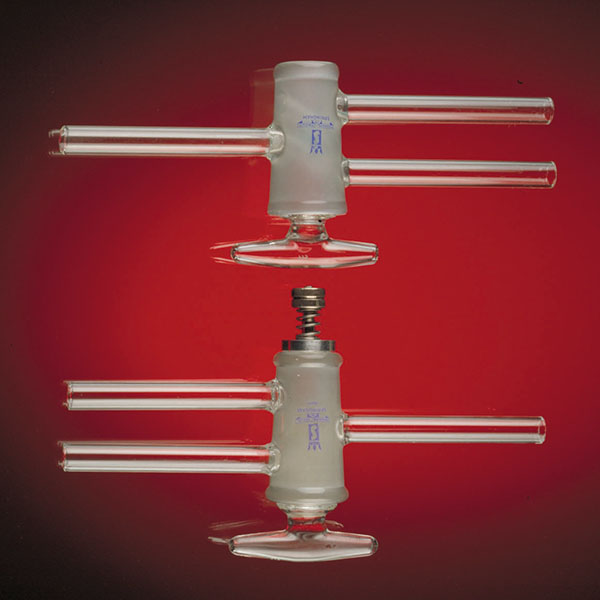

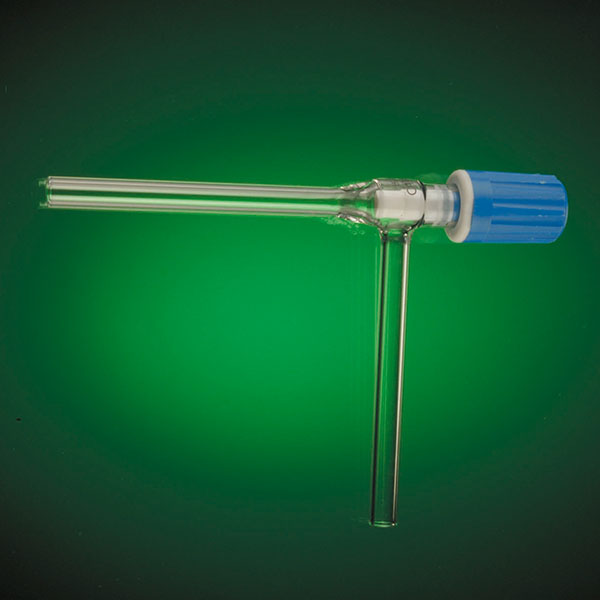

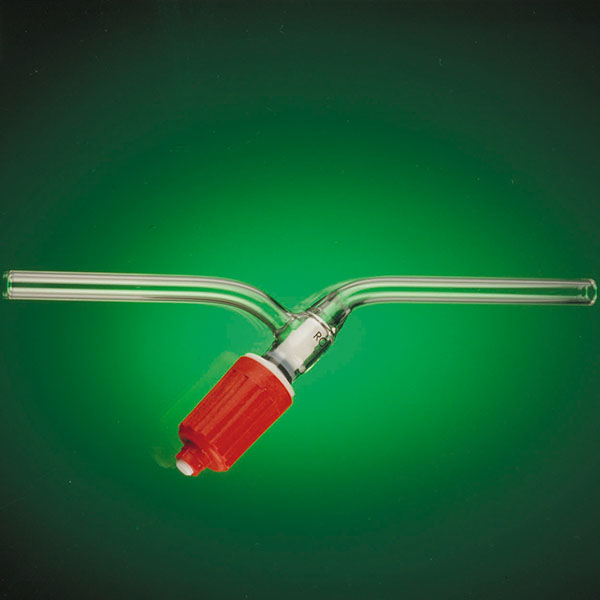

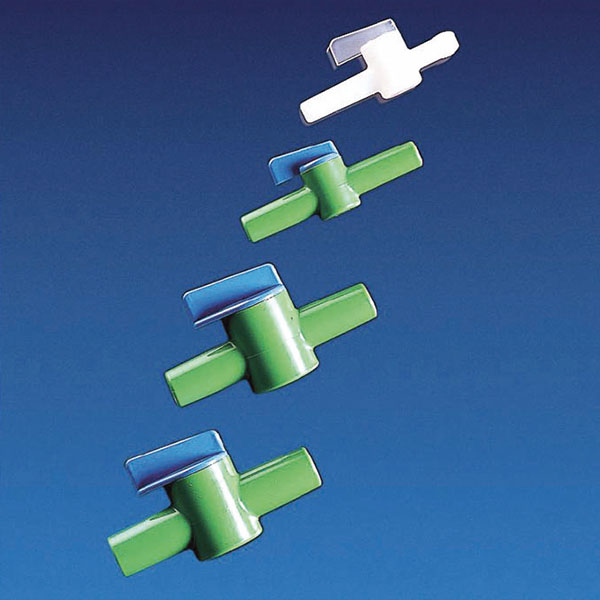

Taps are generally made of glass, and are characterised by a conical structure with a handle, inserted into the corresponding ground glass female joint. Their handle can be made of glass or Teflon. The female joints in which the taps are inserted connect two glass tubes, but there are models of many varieties. For example, a tap model that connects three glass tubes is called a 'three-way tap'. Furthermore, taps can be connected to glass tubes either in a straight line or at an angle. Of course, it is possible to make different taps depending on the required characteristics. For example, taps with a double oblique structure are used in the Schlenk Line and allow vacuum and inert gas to be applied from the same tap.

Vacuum Taps

Vacuum taps must guarantee a sealing performance under vacuum conditions. Consequently, they must be of high quality. They can be made of glass or PTFE (polytetrafluoroethylene). The main difference between the two categories is that glass vacuum taps need to be lubricated. In fact, damage to these must be prevented. In contrast, PTFE taps do not need to be lubricated. In addition, these can also be adjusted to a higher gradation, as opposed to glass taps, which are limited to an 'on/off' flow.

Care of taps

Taps must be handled with extreme care. It is not necessary to force them closed or open, as this would risk damage or breakage. If, for example, it is difficult to close a Teflon tap, it could be misaligned or already damaged. Forcing its movement could result in irreparable breakage of the glass component.

.